New Delhi: From East to West, India today is spearheading major transnational transport corridors that will eventually link the Atlantic to the Pacific via Asia.

The Prime Minister Narendra Modi-led Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government is pushing hard for these corridors — the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEEC) initiative through the Arabian peninsula, the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) in the West to the trilateral highway in South East Asia and the Chennai-Vladivostok route to the East.

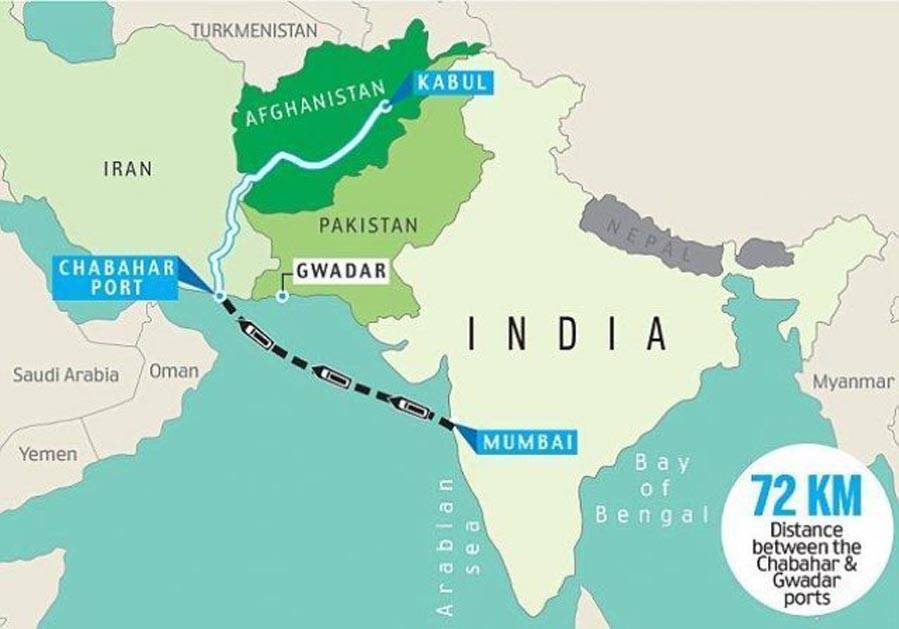

While IMEEC aims to connect India to Europe via the Arabian Peninsula through rail and sea links, INSTC — conceptualised two decades ago — spans 7,200 kilometres, encompassing ship, rail, and road routes connecting India through Iran and Central Asia to Russia. The Chennai-Vladivostok corridor holds promise for India’s connectivity with the Russian Far East.

The envisaged corridors will see multiple countries in action, some of whom are seen as adversaries and not partners.

As India goes ahead with these projects, ThePrint is doing a four-part series deep dive into the plans.

Government sources told ThePrint that India views these transport corridors as necessary to meet its fast-paced economic growth and as a tool to nurture strategic alliances.

This comes at a time when, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), India is the fastest-growing economy in the world — poised to grow roughly at 7 percent.

Whether Houthi attacks in the Red Sea or the 2021 Suez Canal blockage that halted global shipping for six days, countries have been exploring safe and alternate routes for goods transit.

As US President Joe Biden said, while announcing the IMEEC at the G20 Summit in Delhi last September, “Economic corridors — you’re going to hear that phrase more than once, I expect, over the next decade.”

Though IMEEC — which seeks to connect India to the Gulf and Europe — is a new venture, the INSTC was conceptualised in 2000, before China launched its ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013.

The INSTC was initially intended to send goods from India to Russia through Iran. The first set of goods was transited through it in July 2022 via Iran’s Bander Abbas port.

Illustration: Prajna Ghosh | ThePrint

The INSTC has been viewed as a viable solution for sanctioned countries like Iran and Russia.

“The INSTC was designed to transport goods between India, Russia, Central Asia and Europe. In the best case, IMEEC can only transfer cargo between India and Europe. Therefore, IMEEC can never replace the INSTC,” Iran ambassador to India Iraj Elahi told ThePrint.

Of late, External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar has started to link the IMEEC and another regional connectivity project — the India-Myanmar-Thailand (IMT) trilateral highway.

“Together, they can be veritable changers connecting the Pacific to the Atlantic,” he said in February, adding that there is a need for lateral “land-based” connectivity in the Indian Ocean.

The highway, though believed to be 70 percent complete, has been shadowed by the security situation in Myanmar as well as the neighbouring state of Manipur, which has seen a bloody conflict between ethnic groups.

Due to “political instability” along the India-Myanmar border and south Myanmar, where rebel groups are active, there’s no guarantee that the 160-km road linking the border of Tamu/Moreh to Kalmeya and Kalewa — the first segment of the highway — won’t face “damage”, people familiar with the matter told ThePrint.

Illustration: Prajna Ghosh | ThePrint

Growing global push for economic corridors

India has attempted to build regional economic corridors and transport connectivity long before the Chinese BRI.

The INSTC was first conceptualised in 2000 and remains incomplete as of 2024, while construction for the IMT trilateral highway began in 2012.

The trilateral highway has been a part of the South Asia Subregional Economic Cooperation (SASEC) programme since 2001. The programme brings together Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Myanmar, Nepal and Sri Lanka to promote cross-border connectivity and facilitate faster trade connections among the countries.

It has $18.41 billion in investments from the Asian Development Bank (ADB). The ADB believes that SASEC involves the “leveraging of infrastructure connectivity to unlock the full potential of markets.”

The advent of the BRI — touted as the “project of the century” by Chinese President Xi Jinping — which has seen close to $1 trillion in investments made by Beijing, has changed the geopolitical conversation surrounding connectivity projects.

The Maritime Road and Silk Road economic belt (hence the original name ‘One Belt One Road’) saw China attempting to fill a vacuum in infrastructure spending, which existed globally.

The G7 recognised this infrastructure gap in 2021 when it announced the Build Back Better World (B3W). The B3W aimed to bridge the $40 trillion infrastructure gap in the developing world and offer an alternative to the BRI.

The efforts were eventually renamed the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII), on the sidelines of the G7 leaders’ summit in Hiroshima, Japan, in 2023.

A major project announced as a part of the PGII a few months later in September 2023 was the IMEEC — a corridor connecting India to Europe via West Asia and offering an alternative route to the Suez Canal — a known choke point to global trade.

In a flattering encomium on the necessity of such corridors, Biden, during the G20 leaders’ summit in New Delhi, said, “The world stands at an inflection point in history. A point where decisions we make today are going to affect the course of our future — our future — all of our futures for decades to come. A point where our investments are more critical than ever.”

The IMEEC would see goods shipped from India’s Western coast to the UAE and travel via rail to Saudi Arabia and then possibly through Jordan to Israel. Neither Israel nor Jordan signed the original MoU.

The project could see the port of Haifa in Israel being a part of it. From this port, operated by the Adani Group, the goods would be shipped to Europe, where Greece — another non-signatory to the corridor — claimed the port of Piraeus to be the gateway to the continent for European goods.

Illustration: Prajna Ghosh | ThePrint

However, if such a project would come to fruition and offer an alternative to China, it should be noted that the majority stakeholder of the Piraeus port and its operator is a Chinese state-owned company — China COSCO Shipping.

Glimpses of global alliances

As a part of the BRI, in 2017, China hosted the first Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation (BRI Forum). The event drew participation from 29 heads of state and governments, along with delegations representing over 130 countries. India refused to attend the forum and even declined to join the initiative.

The third forum held in 2023 saw the Taliban in attendance despite a lack of international recognition — underscoring Beijing’s growing ties with the organisation that has been in power in Afghanistan since 2021.

Similarly, projects such as IMEEC, INSTC, and the IMT trilateral highway have garnered interest from some countries, while others have opted to remain aloof.

The IMEEC has seen interest from Israel, a country that has only in recent years been able to normalise ties with countries in West Asia, after the 1990’s.

Turkey proposed its own “Iraq Development Road” right after IMEEC was announced in September 2023.

The project would see goods transferred to the Grand Faw port at the tip of Iraq and then carried by land to Turkey before they reached Europe. According to reports, the UAE and Qatar are keen on such a project.

Meanwhile, in a visit to India by Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis in February 2024, Greece — a country with a history of tense relations with Turkey — staked its claim to being the gateway to Europe.

Membership in such projects also impacts a nation’s foreign policy standing. For instance, Italy, the only G7 member a part of the BRI, withdrew from the Chinese-led project in 2023 and is a founding signatory of the IMEEC MoU.

This is the first in ThePrint’s four-part series on India’s envisaged transnational transport corridors.